On June 25, parliamentary elections took place in Albania in which current PM Edi Rama’s Socialist Party (SP) took a majority of 74 seats in the 140-seat parliament, defeating main opponent Lulzim Basha of the Democratic Party (DP). The Socialist Movement for Integration (LSI) lost its role as kingmaker, although it took another three seats to increase its total of 19. It is the first time since the communist era that a single party has taken full control.

Many dubbed the elections a crucial moment for Albania’s bid for European Union membership, considering it a test for democracy. As the elections were postponed for a week after a stalemate between the SP and DP, some 400 international observers were eager to see how Albania took on the challenge.

Among these were 30 observers from the Danish youth organisation Silba who were deployed in five electoral districts in the capital Tirana. Silba conducts Election Observation Missions (EOMs) since 2003 and has a track record of 47 EOMs to 15 countries, although its mission to Albania was a first.

Close to home or miles apart

For some participants, Albania hits rather close to home. Arben, 25, was born to an ethnic Albanian father, grew up in Germany and now studies in Denmark. He joined the mission both out of personal interest and to explore the country where part of his roots lie. As he speaks Albanian, he considered it “a good opportunity to get a first-hand impression of the state of democracy in the country and what the Albanians want in that regard”.

Other participants admitted to being drawn in precisely because Albania is quite unknown and considered so different to Denmark. Andreas, 36, a Copenhagen policeman turned student, said he knew little of the country before going there, considering it an adventure that would help him gain needed experience in the international arena.

Both state that they felt welcomed by the Albanian people.

“People told me they were happy that we were here,” said Arben.

“They care about the international community and their position in it. I got the impression that the voting is taken more seriously when international observers are there.”

“It is a bit like an exam,” added Andreas.

“When we arrive, people start thinking about the procedures again. In that sense I think we enhanced the quality of the elections a bit.”

A good impression overall

According to the organisation’s preliminary report, the voting process was generally well organised, despite some minor irregularities. The voting was extended for an hour due to the low turnout, which caused some chaos, and the counting centres seemed somewhat unstructured, causing the counting to start in the middle of the night. The overall rating, nonetheless, was “(very) good” by the vast majority of teams.

The biggest concern were the party representatives present in and outside the polling stations, who appeared to keep track of ‘their’ voters.

“Observers noted that PSOs [Party Station Officials] would systematically and in a deliberate manner let the party representatives know a specific number attached to the voter’s ID. This could potentially lead to patronage and social control, since party representatives […] seemed aware of identities of voters that had not yet shown up”, the report reads.

The voter turnout in the 2017 elections was historically low at 44.9 percent. The reasons given were the hot weather and the Ramadan celebrations taking place on Election Day. But public trust in the political system is also poor. When asked, 79 percent of the Albanians said they had “(basically no) trust” in political parties, according to a 2015 opinion poll by the Institute for Democracy and Mediation.

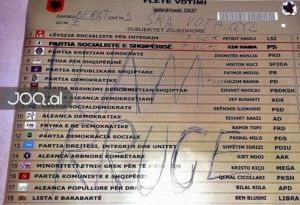

Illustrative were photos of spoiled ballots on social media with voting papers signed with texts like “Fuck you!” and “We don’t vote for you – we want streets!” in a bid for better infrastructure. Ironically, these elections marked the first time taking pictures in the voting booth was prohibited by law.

Learning from one another

The presence of international observers during national elections in places like Albania tends to be seen as a way to secure and possibly enhance trust in the democratic process.

But Andreas is keen to point out another issue: enhancing understanding.

“We have learnt so much from NGOs, professors and locals during this week and we will take this information back and share it,” he said.

“Our local interpreter also learnt something from us I believe. This can help the country in the long run.”

It remains to be seen where the country will be in four years when the next elections are due. It is not unlikely Silba will be there to observe again.