Surrealism as an art movement began in Paris in the 1920s, partly as a response to the horrors of the First World War and the Great Depression.

André Breton wrote its manifesto and its adherents were concerned with notions of freedom and inward exploration, following up on the ideas that Freud put forward on dreams and the subconscious.

Although his work predated surrealism, the group was influenced by the mysterious, classically-inspired pictures of empty town squares and geometric objects painted by Giorgio de Chirico. The ‘melting watches’ of surrealism’s most famous exponent Salvador Dali are also familiar to many.

A healthy sign

The current exhibition carries on a trend by which, to their credit, galleries are trying to bring unjustly forgotten women artists back into the public consciousness. Here, we have works by Denmark’s Franciska Clausen and Rita Kernn-Larsen and the half-Norwegian, half-American artist Elsa Thoresen, who was married to a Dane.

Clausen and Rita Kernn-Larsen were both pupils of Fernand Léger at various times, which is evident in their work.

However, although they share a number of similarities, the three women’s styles and output are different. Clausen mostly painted small gouaches and only a few larger paintings. She was also criticised for being in Léger’s shadow (they were also personally involved), but although her work shows his influences – and she also actively collaborated with him on some pictures – she was ultimately drawn to more abstract styles.

Clausen exhibited several times in Paris and New York, as well as in Denmark in 1935 and 1937, but after her father died she returned to Åbenrå, where she dropped modernism and made a living as a portrait painter until her death in 1986.

A Miro influence

Kernn-Larsen also lived abroad, training first in Oslo and then moving back to Copenhagen and on to Paris in 1929 where she became a pupil of Léger. Kernn-Larsen’s surrealist period lasted from around 1935 to 1945, during which time she exhibited at major exhibitions in Paris, London, New York and back home in Copenhagen. Here work seems to have a more playful aspect than that of Clausen, and she uses shapes and forms that can be seen in the work of Miro.

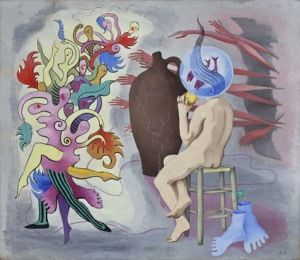

In her picture ‘Festen’ (the party) from 1935, we see a nude female figure seated on a stool from behind, but the head has been replaced by a goldfish bowl-like object. To the left are a jumble of dancing abstract figure shapes, but to the right the figure is being clutched at by hands and arms coming into the picture space. Some have interpreted this to show a personal dilemma faced by the artist, with the arms representing the threatening onset of the demands of motherhood.

One of Clausen’s works, entitled ‘Vasen og Piberne’ (vase and pipes), also juxtaposes the male/female spheres. The picture is divided down the middle and the left-hand side shows a bowl with five pipes sticking up from it. The right-hand side is a vase with a drooping flower and what appears to be a seed falling from it. A butterfly hovering above.

Magritte and onwards

The final member of the trio, Elsa Thoresen, was introduced to surrealism by her first husband, the Danish painter Vilhelm Bjerke Petersen, when they met at the art academy in Oslo. She studied in Belgium from 1927-1929 and influences of the Belgian artist René Magritte are evident in her work.

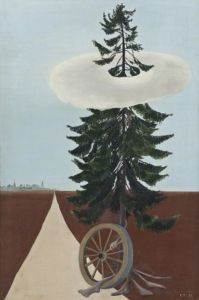

Her ‘Klassisk Landskabe’ (classical landscape) shows this quite well. A road leads towards (or away from) a city, and there is a wheel stopped at the base of a tree that shoots up somewhat phallically through a white ring of cloud and onward.

This exhibition contains many interesting works by all three women and it is to be hoped it may serve to bring them back into their rightful place in Danish and European art history.