One hundred ‘nisser’ elves for every baby Jesus – one can’t help but notice the imbalance in Danish Christmas decorations. One might accuse the Danes of having lost sight of the ‘true meaning of Christmas’, but if you ask the average person on the street, he will probably smile and say: “Well, we Danes are really pagans at heart.”

And he’s not lying, particularly when it comes to Christmas, as this is a truth that runs back at least 3,000 years.

Jul be next, king

Often listed as a synonym for Christmas, the term ‘Yuletide’ predates the birth of Jesus and very possibly the whole of the Iron Age.

The word ‘jul’ is probably derived from ‘hjul’ (wheel), while ‘tid’ means ‘time’. Considering the cyclical nature of the solar year, ‘wheel time’ makes sense. At the end of December came the winter solstice, a day of tremendous importance in ancient agricultural societies because the days start to lengthen again – signalling the continuous cycle of the seasons.

In prehistoric Europe, the winter solstice was a time for the sacrifice of the sacred ‘king’ – a tradition that no doubt many republicans would like to bring back today. This king was believed to be the living incarnation of the ‘grain spirit’. For one year the king was given sacred status among the community – then on the winter solstice he was sacrificed to the gods.

His death brought about two effects: first, all the sins of the village were atoned for, and second, fertility was assured for the following year’s crop. This fertility was secured as the king’s remains were sown into the fields in the following spring.

Over time, the sacrifice shifted from a human to an animal. Still, with the arrival of every winter solstice, a sacrifice had to be made. In the Viking era, this sacrifice was usually a goat or boar. With the arrival of Christianity in the 9th century, the sacrifice became symbolic, and a straw doll replaced something living.

Dollies and dough

In ‘The Golden Bough: A Study of Comparative Religion’, Sir James Frazer describes this symbolic animal – which is often known as either a corn dolly or corn mother – and how it would sit on tables through Yuletide before being burned on Christmas Eve, thereby purifying the house.

In modern times, the descendant of the corn dolly in Denmark is the ‘julebuk’ (barley goat). Today it survives the furnace and returns to the box of Christmas decorations. Some are purchased as a tourist curio and then no doubt mistaken for Spanish donkeys.

Another corn-related tradition that evolved from the sacrifice was the baking of a boar-shaped loaf using the last sheaf of grain harvested in the year.

“All through Danish Yule, the Yule Boar [loaf] stood on the table,” explained Frazer.

“Often it was kept till sowing time in the spring, when part of it was mixed wit h the seed grain and part given to the ploughman and the plough horses or plough oxen in expectation of a good harvest.”

Of course! Ambrosia!

However, the julebuk and Yule Boar loaf only have a peripheral link to ancient paganism in comparison to nisser.

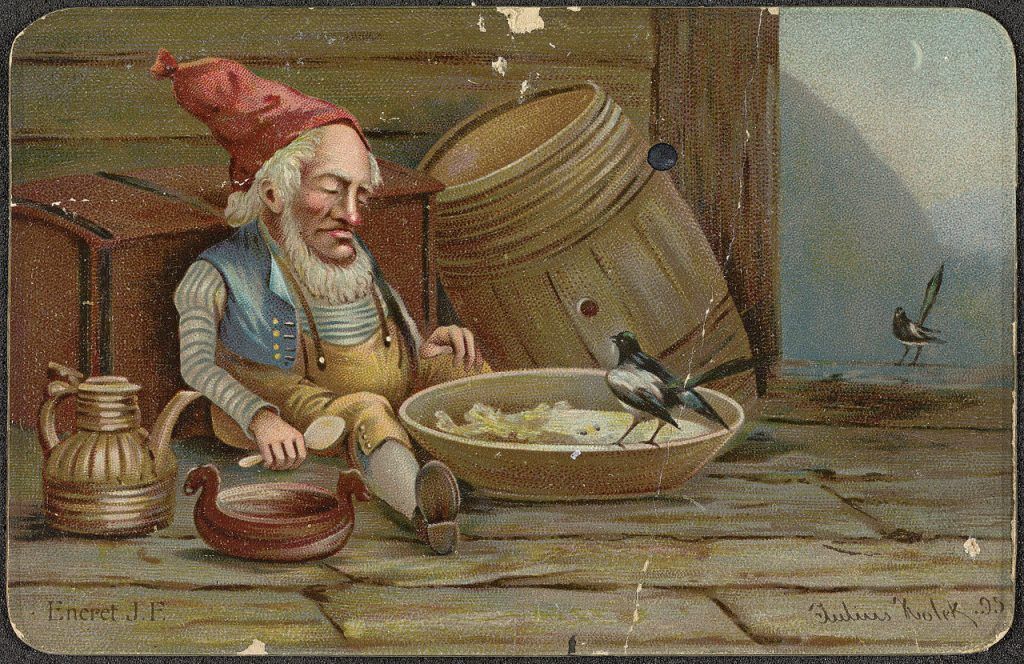

In every shop, you see them dressed in their red suits with their beards and mischievous smiles. While the nisser are portrayed as cartoonish happy-go-lucky gnomes today, they are the surviving remnants of the pagan gods.

With the arrival of Christianity, ancient religions were pushed out of the cities, but still thrived among the ‘pagusi’ (pagan villagers). Among the farmers, ancient gods took the form of ‘gårdboer’ – protecting spirits of the ‘gård’ (farm).

These spirits usually lived in the lofts of houses or barns and demanded offerings in order to ensure a good crop. This was not isolated at Yuletide, but demanded all year round.

Nisser: best not pissed

However, during Christmas time, each gårdbo required the best of the year’s grain (or imported rice), mixed with butter and the most valuable of commodities: sugar.

In this way, the tradition of ris á l’amande (rice pudding) was born. As the tradition is today, nisser require rice pudding on Christmas Eve – otherwise, they will play pranks on the house.

Nowadays, these pranks are practical jokes, but in ancient times they were serious. Nisser were blamed for the death of livestock and spoiling of food stores, and sometimes even for still-births and premature deaths.

In fact, one of the etymological origins of the word ‘nisser’ may be from the old Norse word for ‘infection’.

Named after Niels?

However, a more likely way in which the nisser got their name was through a belief that is common in many religions. In many faiths, including Judaism and some denominations of Christianity, it is a sin to say God’s name.

In medieval Denmark, this faith also prevailed, but it came with the usual Danish flourish: though it was a sin to say the name of one’s gårdbo, one could nickname him. But what name in Danish should a spirit have? It had to be simple enough to say, while also general enough so as not to insult the gårdbo.

The agreed answer was Niels, one of the most traditional Danish names. Thus the nisser, the country’s most traditional Yuletide symbol, was duly named.