Denmark will cease producing distinctive, provocative and ambitious filmmakers like Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg should the current funding criteria of the national film institute, the DFI, continue as it is today, claim industry insiders. The DFI makes arbitrary decisions, they argue, and the whole process discourages risk taking.

“It is a very professional organisation and it is guaranteed to produce good films like ‘A Royal Affair’,” an up-and-coming filmmaker, Søren Juul Petersen, told The Copenhagen Post. “However, as with any other industry, if you don’t innovate, you will die. Maybe not in the short-term, but in the long run, you will choke on your own success.”

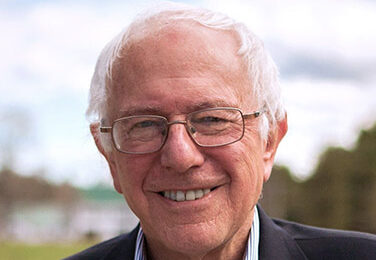

Lars von Trier, whose upcoming erotic film, ‘Nymphomaniac’ will once again push boundaries on screen, realised all this early on in his career. To maintain creative control he knew he needed to be financially independent, so in 1992, along with producer Peter Aalbaek Jensen, he started Zentropa, a decentralised and autonomous production company that is now the largest in Scandinavia.

Less experienced Danish filmmakers, however, are struggling to find avenues for innovation and development that circumnavigate the historically state-supported film industry. While life on the ‘outskirts’ of the film industry exists, the DFI has strict terms for financial support and, large as Zentropa is, it cannot compete with the DFI’s scope, thus leaving many scrambling for crowd funding sources and private investors for film development opportunities.

“I have spoken personally to both accomplished filmmakers as well as the talented undiscovered in Denmark, and both, interestingly enough, come to the same conclusion,” explained Alex Archimbaud, an independent filmmaker, to The Copenhagen Post.

“That conclusion is that the fate of their project lies in the hands of a single consultant − their choices will always be based on their tastes, statistical/psychological speculation, personal experiences, references, and ultimately, in many instances, quotas imposed, loosely or heavy-handedly by an ageing bureaucratical system. That’s a scary concept. All of a sudden you have a single person who can open or close the door to your project.”

Søren Juul Petersen, a film producer who is the head of the film production company Zeitgeist, experienced this obstacle in the making of ‘Det Grå Guld’, his latest movie which is scheduled to come out on March 28.

“It’s a dramatic comedy,” he told The Copenhagen Post. “About three elderly people deciding to rob a bank in order to get money for the rest of their lives. It is a project that was never funded through the DFI or any of the radio stations. It was turned down because they predicted that there would not be an audience for such a film. Strangely enough, senior people are going to the movies more than ever now.”

Initially, the New Danish Screen, founded in 2003, was founded to encourage innovation and new ideas, and to support aspiring film producers like Søren Juul Petersen and Alex Archimbaud. It is a talent development subsidy scheme which, according to the Danish Film Institute website, aims to utilise “the energies and directions of talented creators, rather than guide them in well-defined directions”. Approximately 15 million euros have been allocated to the New Danish Screen over the course of 2011-2014. But less experienced filmmakers are still not reaping the promised benefits.

The DFI again took action in 2010. The DFI’s year-long dialogue project Spørg & Lyt (Ask & Listen), involving 250 stakeholders from the film industry, highlighted the desire to see micro-regulation replaced by a dialogue between parliament, the DFI and the film industry as to what the results of film subsidies should be. The Danish Film Institute then published a proposal of what is needed to ensure a diverse and sustainable film culture in Denmark in the future, entitled ‘Set Film Free’.

Changing the structure of state funding for Danish film production seems risky, especially when Danish films have earned major love from the Academy Awards in recent years. Susanne Bier’s drama ‘Hævnen’ (‘In a Better World’) snagged the best foreign film trophy for 2010. ‘En Kongelig Affære’ (‘A Royal Affair’), starring Mads Mikkelsen, was a recent nominee for Best Foreign Language Film.

But Petersen remains unconvinced. In a letter he wrote in 2007 to Henrik Bo Nielsen, the head of the DFI, Petersen asked: “Why aren’t there any recent graduates from the Danish royal film school who are starting their own companies? Why are there no recent media studies graduates taking their chances at being independent in the film industry? And why are there no established producers from large companies who dare to create their own?”

And earlier this month, Petersen confirmed that he is still just as worried about the future of Danish film as he was six years ago.

“Nothing has changed. I think that article is something that I could have written last week.”